Though the Vietnam War left physical, mental and emotional scars that remain today, it also prompted the first physician assistant training programs. With this experience, returning veterans had a meaningful career option when their military service ended.

Today, PA training includes many of the same college classes as medical students but without the residency requirement. It has been invaluable over the past 50 years in delivering care to underserved rural areas and Native American reservations, its original intent.

Learn more: Find a Sanford location near you

Like a lot of health systems, Sanford Health relies on more than 100 PAs to serve as physician extenders. They give care that a medical doctor would otherwise provide where it’s not possible or practical to have an MD.

Enlarge

(Photo by Sanford Health.)

When Jason Rogers, a former Sanford Health PA in Bismarck, North Dakota, took the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery test, or ASVAB, it told him he should practice medicine. His passion was in aviation, so after joining the Army and learning to fly helicopters, Rogers switched to a medical unit and learned about the PA program.

He completed that training and was sent to a flight surgeon course, which allowed him to both fly and care for aviators, then went through training in emergency medicine, occupational health and ultimately the ear, nose and throat program.

Growth in physician assistant career

“Where I’m at, I’m easily able to move from career to career,” Rogers said. In fact, in September of 2019, he left Sanford Health and moved to Fort Worth, Texas.

He was part of the North Dakota National Guard’s 81st Civil Support Team, one of 57 teams in the U.S. and its territories that attend high-profile events and stand ready to respond to alerts of unknown substances. The team has staffed the presidential inauguration, Boston Marathon and other major events.

Looking for more news like this? Subscribe to our newsletter

His role was to medically clear everyone who put on a hazardous materials suit, monitor them and check them afterward. If a response was needed, Rogers also helped coordinate by identifying the number of hospitals necessary and aiding incident command.

As part of his military service, he was required to spend 20 percent of his time in a medical treatment facility. That is what led him to Sanford Health in Bismarck, where he examined ear infections, read and interpreted hearing test results and provided preoperative and postoperative care, among other things. He saw people young and old who often traveled hundreds of miles from rural areas and reservations.

Like the original PAs of the 1960s, Rogers fulfilled a deficit in health care by serving as a physician extender to those populations.

Enlarge

(Photo by Sanford Health.)

UND starts third program in U.S.

That’s something that Robert Eelkema, M.D., knows a great deal about.

At 87, he still lived in Grand Forks, North Dakota, where he started the third physician assistant training program in the U.S. at the University of North Dakota, which graduated its first class in 1972.

Eelkema saw around him many physicians in rural North Dakota retiring without replacements. About the same time, Duke University was launching the first PA program, followed by the University of Washington, which began a second program focused more on rural areas, which Eelkema used as a blueprint.

Those original efforts sought to draw on veterans returning from Vietnam who had experience as Army medics or Navy medical corpsmen. After the training, which typically lasted two years, the new PAs joined the physician they trained under in practice and earned a starting salary between $8,000 and $12,000, or $54,000 to $81,000 today.

Physician shortage

Following World War II, physicians trended more toward specialization, in part incentivized by federal policies that reimbursed specialists at higher rates than generalists. This reduced the number of generalists at the same time that the overall supply of physicians also trended downward.

Some areas felt this shortage much more acutely than others: rural areas, American Indian reservations and inner cities. In rural areas, in particular, doctors felt stretched to the breaking point, and many left for larger suburban areas where the workload would be more bearable.

While doctors traditionally protected their field from encroachment by other professions, given the shortage, they welcomed the role of PA. A physician assistant would cover the routine tasks of a medical doctor, freeing up the physician to attend medical seminars and professional meetings without having to close his or her practice.

The Vietnam War witnessed innovation in efficient delivery of medical care by trained personnel in combat. These returning veterans brought home with them experience in medical improvements and team care.

At the same time, to deal with the physician shortage and health care disparities, the country experimented with a number of new approaches to health care delivery, including rural primary care clinics and the creation of new health professions, among them physician assistants. It was thought that PAs could remedy geographical disparities by being trained to work in rural clinics, and that veterans could fill this role.

Promoting PAs in popular culture

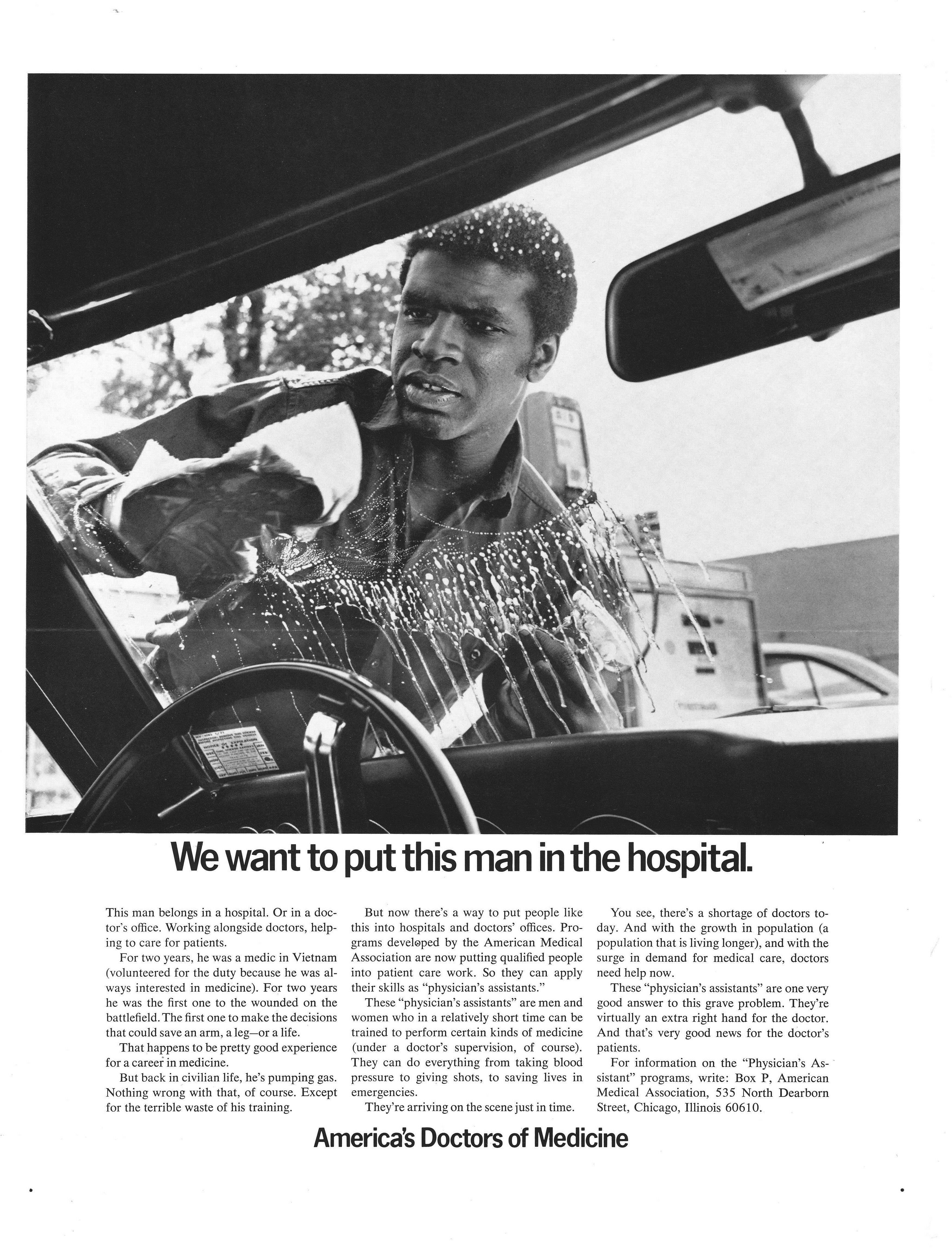

To highlight the need for more health care providers, the American Medical Association bought an ad in Life magazine. It showed a Vietnam veteran washing a car windshield, with the caption, “We want to put this man in the hospital.” The explanation clarified that he had served as a medic in Vietnam but was now pumping gas. Instead, he should have been part of the PA program.

Enlarge

(Photo courtesy American Medical Association Archives.)

Similarly, the AMA’s president wrote a four-page piece for Reader’s Digest, another best-selling periodical, offering a “Prescription for the Family-Doctor Shortage.” That solution was, of course, the physician assistant. The AMA advocated that physicians pass all routine functions onto PAs. The article urged readers to show it to their doctors to gain support for this crucial medical reform.

The promotion of PAs even made it into the funny pages. In one strip of Little Orphan Annie, an ex-medic and corpsman shows a brochure describing paramedic and physician assistant programs. Completely out of sync with other strips in the series, even it set aside a day to promote PAs.

PAs in North Dakota

Because of the state’s large rural and Native population, the University of North Dakota became an early adopter of the PA program. UND graduated the third class in the U.S., after Duke and the University of Washington.

“We went ahead full steam without a lot of knowledge,” Dr. Eelkema said. “But we knew that the people needed help and that the people coming into the program were bright and well-trained in trauma.”

The PAs were generally well received.

A 1971 Grand Forks Herald newspaper article highlighted Velva, in north-central North Dakota. The town had grown from 2,500 to 5,000 people in just one year. With just one doctor, who happened to be sick on a given day, a dozen patients would have had their appointments canceled. They were given the opportunity to see his PA instead. All but one said yes.

Perhaps even more surprising was the degree of interest in the program. The article reported that the 20 men in the first class were chosen from more than 500 veteran medic applicants.

The UND program also focused on Native American health care and received a large grant from Indian Health Services. In 1974, 10 American Indians graduated from the program to work on eight reservations in North Dakota and Montana.

Their help was desperately needed. Life expectancy was 43 years, infant mortality was 3 to 4 times higher than elsewhere and tuberculosis afflicted 4 1/2 times as many Native Americans as whites, among other stark health disparities. There were only 56 Native American doctors in the United States at the time, and only three of them worked in Indian health care.

Adjusting to rural life

While the demand for PAs was high in rural areas, some of them didn’t adjust well to small-town life.

“The big problem was that a lot of the independent-duty corpsmen were from the big city,” Dr. Eelkema said. “We had a hard time keeping them in the places we were training them.”

And after four or five years, there were no more returning veterans to draw on. So the UND PA program started to pull more students from the general population.

Enlarge

(Photo by Sanford Health.)

Sanford Health PA Ann Owens is one such person who attended the UND program many years later. She went to nursing school and practiced for five years in Bismarck. Then, she went back to UND to become a family practice physician assistant. She completed her preceptorship in the area of Hillsboro, North Dakota, and Halstad, Minnesota, where she grew up.

“Once I had kids, I knew I wanted to be back around my family, small town, the whole works,” Owens said. “I knew that was going to be pretty important.”

She enjoys working in the area because of the familiarity. She’s also fulfilling a health care need that would become a steep deficit should she leave. The region has just two medical doctors, one PA (her) and no nurse practitioners. However, Owens does not feel overburdened and said they enjoy flexibility among them.

On a recent day, Owens saw patients from 2 weeks to 63 years old for a variety of ailments. She cared for concussions, a rash, pneumonia, chest pain, behavioral problems, and the usual winter coughs, colds and influenza.

It’s never boring.

“Whatever your schedule looks like in the morning is not what it will look like throughout the day. Things change as the day goes on,” she said.

The PA profession today

Like Owens, Rogers said he enjoys his career path.

Less than 1 percent of PAs pursue a medical degree. That statistic is attributed to high job satisfaction and low burnout. Also, there’s ample opportunity to move from one subspecialty to another, he said.

“I would not become a doctor if I could do it all over again,” Rogers said. “I feel privileged to serve my country and to do so as a PA.”

Learn more

- Key dates in history of Vietnam and PA training

- Vietnam DJ serves up music and memories at Sanford Vets Club

- Health care in your hometown? It’s about family, community

This post was originally published on March 23, 2018.

…

Posted In Clear Lake, Detroit Lakes, Dickinson, Grand Forks, Jackson, Jamestown, Luverne, Mayville, Minot, Mountain Lake, People & Culture, Physicians and APPs, Rock Rapids, Rural Health, Sanford Stories, Sheldon, Thief River Falls, Tracy, Veterans, Wahpeton, Webster, Westbrook, Windom