Some people have the luxury of deeming social distancing an inconvenience. That’s not the case for children and adults with cystic fibrosis.

For them, social distancing is imperative to help stay safe from the lung-ravaging potential of COVID-19.

Even if, as in Ashley Ballou-Bonnema’s case, it separates you — indefinitely — from those you love most. Even if it keeps you from leaving your house. Or sharing living space with your husband, a nurse.

‘Common cold can be deadly’

Cystic fibrosis is, by itself, an ugly, malicious disease. The inherited genetic mutation invisibly spreads thick, sticky mucus throughout the body, challenging families and their care teams to help a person fight each day — essentially from birth — to breathe, gain weight and stave off infections.

The success of this relentless battle can be measured by each birthday and each milestone in life reached. Fortunately, people with cystic fibrosis (CF) are living longer than ever, with a life expectancy now of 40 or more birthdays. And a new medication shows promise to help extend life expectancy even more for the vast majority of patients with CF.

Ballou-Bonnema has spent more than three decades fighting this progressive foe with the help of the Cystic Fibrosis Care Center team at Sanford Health in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. In recent years, she has helped others with their journeys, too.

Their battle has given them expertise in social distancing, while the rest of us had to catch up. They always needed to do it to help stay alive.

People with cystic fibrosis have compromised immune systems. Any illness affecting the lungs poses a great risk to them.

“A common cold can be deadly to us. The flu can be very deadly to us,” Ballou-Bonnema said.

In addition, people with cystic fibrosis must stay at least 6 feet apart from each other because of the risk of cross-infection of the types of bacteria that can grow in their lungs.

“We live by the 6-foot rule,” said Ballou-Bonnema, who has left her Sioux Falls home only a couple of times since mid-March. “So we’re very aware of how that works and what that looks like, and also being masked.”

Isolated for each other

Most of us had never before given a thought to the risk of disease outside our front door. We might learn something from Ballou-Bonnema’s perspective of pandemic precautions.

“It’s a lifestyle, and it’s not an easy one. … It’s uncomfortable, and I don’t like doing it. But I also know if I want a chance at any sense of normalcy in the future or to spend time with people that I love and care about, it’s something that I have to be uncomfortable with,” she said.

“And I think the more that we can be uncomfortable together and realize that this is for one another … the stronger we’re going to come out at the end of this, and the sooner we could possibly come out at the end of this.”

That end can’t come soon enough for Ballou-Bonnema and her husband, Mark Bonnema. First, the pandemic dealt a blow to their long-planned-for trip to Florida in March.

“We had a little staycation, which was great, but I can honestly tell you it was probably some of the hardest two weeks that we had together,” Ashley said.

Because of her disease and Mark’s occupation at Sanford USD Medical Center, working with outpatients who come into the hospital for infusion services, they realized they had to make some decisions.

They converted their basement to a live-in apartment. There, Mark can live and avoid potentially exposing Ashley.

Ashley said they can still spend time together in one of their favorite places: their backyard. “It’s nice to at least have that sense of normalcy,” she said. But otherwise, she said, it’s lonely.

“Sometimes it feels like I’m just like a princess in an ivory tower, shut away and just waiting for the world to find its rhythm.”

Early detection crucial

More than 30,000 people in the United States have cystic fibrosis. Each one inherited a copy of a defective gene from both parents.

Since 2010, newborn screening for cystic fibrosis has been mandatory in all 50 states, a rapid response to advocacy for it. Only five states required it in 2005.

Identifying newborn patients can help start them early on appropriate treatments. Nutritional treatments can help babies gain weight, which is important because mucus in the digestive system can keep nutrients from being absorbed properly. And respiratory treatments can help babies breathe better and prevent harmful infections.

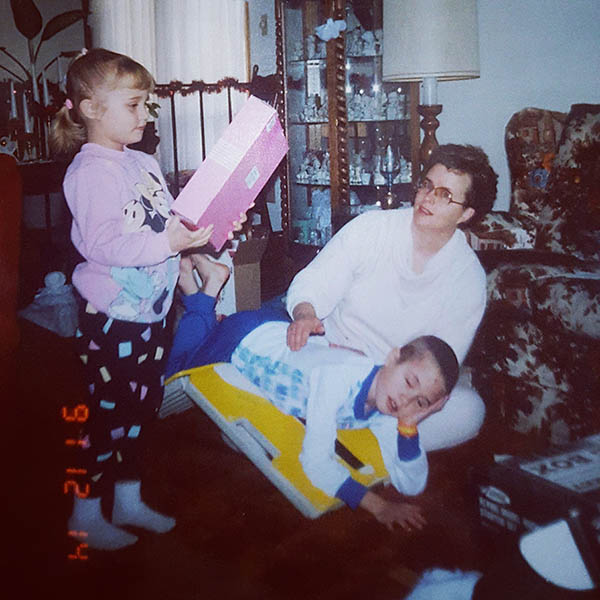

Photo courtesy of Ashley Ballou-Bonnema

Ballou-Bonnema’s brother was born six years before her. Her parents didn’t know they were carriers for a defective gene, and they didn’t know their son had cystic fibrosis until he was about 6 years old, she said. His early childhood before the diagnosis lacked proper nutrition and treatment, and his lungs suffered in the meantime.

“Because his cystic fibrosis was so severe, and he had so much damage from a young age — chronic lung infections, deterioration of respiratory function, complication after complication — he pretty much lived at Sanford,” said Ballou-Bonnema.

She recalls a regular routine of traveling after school with her parents from their residence of Larchwood, Iowa, to the Sioux Falls hospital to be with her brother until 9 or 10 p.m., then driving home and going to bed.

“I always say my jungle gym was the hospitals,” she said about her childhood. “It was IV poles and the child life specialists.”

Ruthless, destructive disease

Ballou-Bonnema had been tested as a newborn, since by then doctors were aware of her brother’s diagnosis. Compared to today, treatment options for her were few. Still, right after her diagnosis, her mom started putting enzyme beads into applesauce to help her thrive with proper nutrition. Then she thinks she was about 5 or 6 when her parents started physiotherapy with her — manual chest percussion.

For 30 minutes at a time, twice a day, one of her parents would rotate her on their lap or on a board and clap her chest and back with cupped hands. This would help loosen the mucus in her lungs and enable her to cough it up. Otherwise, the mucus would clog tubes that normally transport air in the lungs.

“I always say my parents probably had the best forearms,” Ballou-Bonnema said. During the times when her brother was able to come home from the hospital, her parents would do percussion up to four times a day with him.

Ballou-Bonnema feels lucky she had only about six or seven hospital stays while she was growing up. Without early testing, her childhood — and fate — could have looked more like her brother’s.

At age 17, he lost his fight with cystic fibrosis.

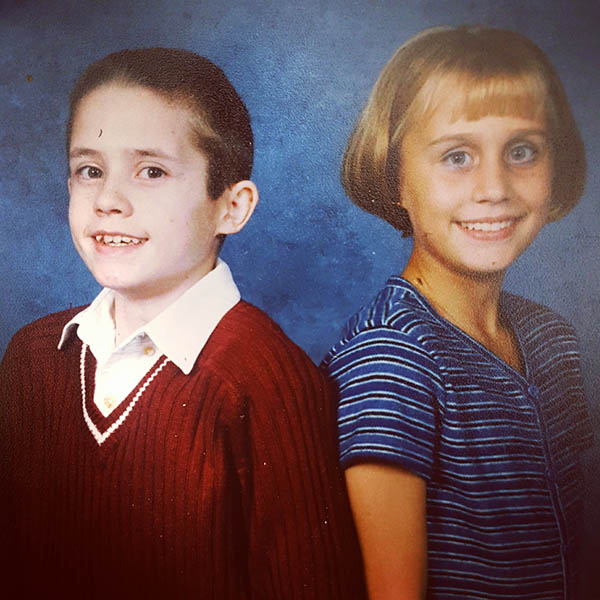

Photo courtesy of Ashley Ballou-Bonnema

“It’s a really humbling thing when you realize that because of your own brother’s suffering and his diagnosis, that you were diagnosed at a young age and able to get treatment that inevitably has saved my life to today,” Ballou-Bonnema said.

“I watched CF really ruthlessly destroy my brother, but I also saw it destroy my parents’ relationship,” she said. A chronic disease that “feels like it controls every entity of your child’s life can really be destructive.”

Hiding cystic fibrosis didn’t work out

Now 33, Ballou-Bonnema has lived well beyond the life expectancy of patients who had CF during the 1980s when she was born. They weren’t expected to live beyond their teens, and adult patients with CF were rare.

Repeated lung infections from bacteria are common — including pneumonia — that frequently require treatment with IV antibiotics. And as people with CF age, the disease typically progresses, while lung function declines.

Ballou-Bonnema saw that happen in adulthood with her own version of CF. She has a chronic infection of an antibiotic-resistant strain of bacteria in her lungs. At one point, she narrowly avoided needing a double-lung transplant.

But for a long time, she tried to hide her disease and appear normal — particularly to her parents, who had already been devastated by the loss of one child. She didn’t want to worry them.

“I just pushed through CF and thought I was stronger and tougher. And that if I just outwilled it, then CF couldn’t touch me,” she said. “That didn’t work out so hot. … The more I tried to hide CF and make excuses for it and run away from it, the more it would present itself in the most unrelenting ways.”

Ballou-Bonnema couldn’t hide her exacerbations — episodes when symptoms worsen — or hemoptysis, when she coughed up blood.

After a friend assured her that the people around her wanted to walk with her on her CF journey, Ballou-Bonnema opened up to them — and to the world. In doing so, she found her purpose for her life.

A triumphant voice

First, at age 27, Ballou-Bonnema revealed to her family, friends and strangers the physical, mental and emotional realities of her disease through her blog, Breathe Bravely.

“I … really wanted it to be a way in which people didn’t see me as somebody who had CF, but that CF was merely my obstacle that I was given in life.”

Later in 2014, though, her disease raged, slashing her lung capacity and spurring conversations about a double lung transplant.

“We know with CF, that’s where your life progresses to, regardless of how hard you fight,” Ballou-Bonnema said. “But I wasn’t ready for that conversation yet, and I had thought it would happen many years from now.”

Nevertheless, she rallied and didn’t need that transplant. As a graduate student pursuing a music degree, she was most grateful her singing could continue unhindered.

Ballou-Bonnema embraces her natural gift and love for singing as a way to also defy CF. She draws deep breaths and strengthens her respiratory muscles.

After graduating, she started teaching local vocal students. She also began the nonprofit organization Breathe Bravely to hold events, fundraise and help others with CF to experience the same freedom and joy she does.

sINgSPIRE program

Breathe Bravely’s vocal instruction program, sINgSPIRE, pairs Ballou-Bonnema and other vocal instructors virtually with people with CF from around the world to work on singing and breathing skills. Contributors to the program include Sanford Health Community Relations and the Physicians Care Sanford Clinic Community Service Committee.

“Just because we have a lung disease that’s trying to steal every breath doesn’t mean that we can’t use every breath that we are given to do something that we really love,” Ballou-Bonnema said.

Her longing to help the sINgSPIRE students overcome the isolation of CF has led her to present two virtual choir events.

The latest choir piece debuted in January featuring 18 singers with cystic fibrosis, ages 13 to 48. Ballou-Bonnema wrote their song, “We Give Voice” — her second piece that emphasizes triumph over CF. Her first was “Until It’s Done.”

The Sanford Health Foundation also contributed funding for a clinical trial to study the effects of singing on pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis, Ballou-Bonnema said.

Waking up, ‘it feels like you’re drowning’

Singing tops off Ballou-Bonnema’s treatment routine each morning. It gives her 20 minutes of pleasure compared to what precedes it.

Her body’s need for sleep turns into a curse by morning, as the hours allow mucus to settle in her lungs.

“When you wake up in the morning and you take that first breath, it feels like you’re drowning,” she said. “So it’s like talking your body into taking a good breath.”

Before starting a new medication, it would take Ballou-Bonnema an hour to feel ready to leave her bed.

Pain in her joints, a complication of CF, causes her to feel like a 95-year-old as well when she gets up, she said.

Out of bed, Ballou-Bonnema takes her medication — about 25 pills — and then does a therapy vest treatment along with nebulizers for about 45 minutes. The vest, which inflates and deflates against the chest wall, performs the chest percussion her parents did manually when she was young to loosen the mucus. The nebulizers help open her lungs and moisten her airway secretions. After that, she sings to feel like her airways are fully opened.

Photo by James Zajicek, Sanford Health

“It’s usually about two, three hours before things are open and ready to move for the day,” Ballou-Bonnema said.

Some days after that, she and CF “can live pretty harmoniously.” Other days, every breath, accompanying chest tightness and strained lung function remind her of its presence.

If she’s going through an exacerbation, she might do a vest treatment in the afternoon. Then she ends each day with more medication and another vest treatment.

“I’m a night owl,” Ballou-Bonnema said, “just because I’ve worked so hard all day to get my lungs opened and breathing. It’s hard to go to sleep at night knowing that you’re going to wake up feeling like you’re drowning.”

Close to her care team

When you make at least four clinic visits a year, take mounds of medication and experience periods of inpatient and outpatient treatments, you tend to get to know the people treating you pretty well. And they get to know you.

Growing up, Ballou-Bonnema said, “I thought it was normal that everybody invited their doctors and their nurses to their birthday parties.”

Those relationships only grew. “A lot of my care team that I had 30 years ago are still really part of my family and still really close to me,” she said.

Sanford Health has the only Cystic Fibrosis Care Center in South Dakota, among a nationwide network of more than 130 centers. It includes a pediatric care team and an adult team.

Ballou-Bonnema’s first pediatric CF doctor, Jim Wallace, still treats lung diseases in children at Sanford Health and serves as director of the Cystic Fibrosis Care Center. She praises the positive influence he had in her life, from her time as a 5-year-old patient to recently, when she had an appointment with him for a research study he’s leading.

Others — although she says she’s forgetting some — include a pulmonologist and nurse from the past, as well as her current nurse practitioner, Nancy Foss. “She’s willing to fight harder than I will sometimes,” Ballou-Bonnema said.

“CF is an exhausting disease, and it’s always nice to have somebody that you can look to that you know is willing to hold you up during the hardest times.”

Of her adult care team, Ballou-Bonnema said, “they’re some of my best friends, just because they know me better than anybody else knows me.”

That includes her pharmacist Stacy Peters. “She truly has made me feel empowered about my own disease and what’s happening with my own body,” Ballou-Bonnema said, “and giving me a voice and feel like my voice has value to it.”

Close monitoring deepens friendship

Peters met Ballou-Bonnema in her late teens. She watched as her CF worsened over time, despite Ballou-Bonnema’s dedication to her therapies.

The antibiotic-resistant strain of bacteria growing in Ballou-Bonnema’s lungs challenged her care team to find medications to use during times of infection. Some medications they resorted to have high risks for serious side effects, such as kidney damage or hearing loss.

Throughout treatments, Peters talked with Ballou-Bonnema to monitor her for side effects and make sure the dosage was appropriate. “During that time, she and I became very close because she was experiencing side effects, and we had to intervene in therapy, and it was a rough road,” Peters said.

Today, the two women are good friends, as are their husbands. When Peters tried to describe her admiration for her friend, she said: “How can you not love Ashley? She inspired me. She’s been a big inspiration in my life to live each day to the fullest.”

She hopes Ballou-Bonnema inspires parents of children with cystic fibrosis, too, from seeing her dedication to treatments, embracing a career and helping the CF community and others.

“I would think that would give them great hope to see that, ‘Oh, my daughter can be that someday. My daughter’s going to have a full life.’”

‘It was a big moment’

Ballou-Bonnema drove over to Peters’ house on an early morning in January to take her first dose of Trikafta. It’s a new medication to fix a defective protein that can potentially improve the quality of life for 90% of people with cystic fibrosis.

“That was one of my favorite days,” Peters said. “I was very anxious to be able to start it because we do have a hard time treating her when she’s ill.”

Peters hopes Ballou-Bonnema will get sick less frequently and be spared the discomfort of some of her difficult treatments.

But personally, Peters said, “Ashley being approved to take Trikafta was an answer to my prayers. So it was a big moment.”

Photo courtesy of Stacy Peters

Mindful of her history of side effects, Ballou-Bonnema joined Peters for breakfast to take her dose that day. Within a few hours, Ballou-Bonnema noticed her mouth and eyes weren’t as dry. “I started drooling just because it was changing the makeup even within my saliva,” she said.

Within three days, Ballou-Bonnema realized she could smell differently — including flowers for the first time.

Another difference: “I’m not salty.”

One telltale sign of cystic fibrosis is salty skin. Parents might taste it when they kiss their baby. The CFTR protein disrupts sweat gland function in addition to lung and digestive system functions. So sweat in people with CF contains much more salt.

After being out on a hot day, Ballou-Bonnema said, when her sweat dried indoors, salt crystals would appear in her eyebrows and on her arms. “I’m the greatest salt shaker that you could bring along to any party,” she would joke. No longer, though.

‘Priceless’ to Ballou-Bonnema

Ballou-Bonnema calls Trikafta a game changer. Her lung function percentage — which typically sits in the high 40s — had improved 8% when she had it checked about a month after starting Trikafta.

“Which was wild. I haven’t seen a number near there, or lived there, in about a decade,” she said.

“The level of our lung function really tells us the progression of our disease. And it’s one of those things that it feels kind of like a ticking time bomb.”

You can do everything within your power to try to counter CF, she said, but if the number keeps dropping, “you are fighting even harder at a losing battle. So to be able to literally and figuratively have the ability to just breathe a little bit is priceless.”

Dr. Rod Parry, the pulmonologist who oversaw the Cystic Fibrosis Care Center at Sanford Health from the late 1970s through the mid-2000s, praises Ballou-Bonnema’s application of singing to CF care as part of that battle.

Dr. Parry had known Ballou-Bonnema from her early days in the clinic, when he was more involved with her brother’s treatment.

But knowing her as an adult, Dr. Parry is impressed by her use of singing as a breathing exercise.

“What she really is doing is helping individuals maintain their current status or improve,” Dr. Parry said. “And this is particularly important right now while we have the new medications just coming aboard, so if people can maintain where they are and then get on the new medication, their future’s much, much brighter.”

Ballou-Bonnema was honored that Dr. Parry attended a Breathe Bravely fundraiser earlier this year, so she could show him what her life has turned out to be. “If he hadn’t had the tenacity and the stubbornness to really start this center here, how would that have affected my life?”

Embracing the moment despite invisible disease

Ballou-Bonnema describes cystic fibrosis as an invisible illness. “On the outside, we can look perfectly normal — and that there is nothing wrong or nothing ranging inside of our body that’s trying to literally suffocate us from the inside.”

But she considers that a reminder for others that people may have a lot going on “behind the façade.” So she urges they give others grace, while also realizing that people with CF are no less capable than other people.

Ballou-Bonnema worries that people with cystic fibrosis, and other underlying health conditions, will become invisible and forgotten during a pandemic in which the best advice for them is to stay home while the rest of the world returns to the activities of the new normal and perhaps neglects precautions.

“It’s easy to forget about our population that demands change and demands other people think outside themselves,” she said.

So far, Ballou-Bonnema has been given 33 years of life to live. She spends countless hours on treatments to add more time to live as bravely, earnestly and passionately as she can.

“I’ve learned … to really just embrace the moment and the day I’m given, because with the nature of CF, tomorrow might be vastly different. So always clinging to how I feel today and making the best out of what I’m given today, it’s helping me survive.”

More stories

- Clinic sees cystic fibrosis patients’ lives lengthen

- Raising a child who has cystic fibrosis

- Carrier test shows what genetics parents may pass to kids

…

Posted In Children's, COVID-19, Pulmonology, Sioux Falls, Symptom Management