In some ways, Jasmine Johnson is a typical high schooler. She enjoys outdoor activities — bicycling and hanging out at a water park. She likes playing ping-pong. And she works part-time at a local supermarket, where a lot of her friends work, too.

But when she drops scientific terms — “RNA extraction,” “intercalated cells” — into a conversation, she’s not just talking about something she read in a textbook.

Johnson’s referring to actual science lab work that she has performed. It’s real-world research with the ultimate goal of helping people. Research that undergraduate college students might struggle to understand.

Johnson traded much of a student’s summer freedom to wear a lab coat, stare into a microscope and encourage cell growth when she was awarded a Sanford PROMISE Scholar internship at Sanford Research in the summer of 2019. PROMISE is short for Program for the Midwest Initiative in Science Exploration.

Ready to join the Sanford team? Apply to be a PROMISE Scholar

During the summer, she mingled with lab principal investigators, postdoctoral researchers and technicians. She worked among other students ranging from undergraduates to Ph.D. candidates, along with three other high school PROMISE Scholars.

Johnson learned lab techniques and public speaking skills. She learned how research fits into the bigger picture of health care and how research could fit into her future.

And she had a lot of fun doing it.

Learning to like science

Johnson started her internship just after her junior year of high school with the air of a driven, intelligent, purposeful young woman who values skills and experience. She considered how decisions now will affect her future goals. She’s social, friendly and not shy about sharing what she thinks in her fast-paced articulation.

That image doesn’t quite fit her description of her younger self. That girl, she said, didn’t really like science and instead preferred math: “It was the easiest thing. I didn’t want to do anything that seemed hard, or I didn’t understand right away, or I had to memorize or learn.”

Freshman biology and sophomore chemistry classes, however, steered her toward science. An advanced placement chemistry class during junior year, with a full college-style lab experience and taught by a former Sanford researcher, clinched her interest. The class had a reputation for being difficult, but taking it convinced her that hard can be good.

Johnson heard about the Sanford PROMISE Scholar program during a college fair at school. The scholar program offers four students a 10-week internship in a Sanford Research lab during the summer before their senior year of high school. It culminates in a scientific poster presenting the student’s work at a Sanford Research symposium. PROMISE scholars earn three undergraduate credits at the University of South Dakota, plus a $2,500 scholarship.

Johnson thought at the time, “That’s really cool, but I’ll never get chosen for it, so I’m not even going to apply.” Then she forgot all about it.

Applying to be a real researcher

However, Johnson never got around to throwing away the flyer. And eventually, she thought maybe she would try for it. Potential PROMISE Scholar applicants are encouraged to shadow in a Sanford Research lab. So to help her decide whether to apply, Johnson spent a couple of hours in a lab researching type 1 diabetes.

“I got to see all the research they were doing for it. … That was really cool,” Johnson said.

She came away with fresh determination.

Johnson wrote the required essays. She submitted letters of recommendation from encouraging and supportive teachers, including her AP chemistry teacher. Then she waited. When she received an interview invitation, she tried to do her best at that.

When Johnson told her teachers she had received the PROMISE Scholar internship offer, they were thrilled. Her AP chemistry teacher, she said, “was so happy, she was bouncing off the walls.”

Friends and family were happy for her, too, though less clear about what this summer job might entail. Johnson wasn’t entirely clear herself.

Nevertheless, entering a lab on the first day of her internship, Johnson stepped into the role of a real researcher.

Trying to help with kidney diseases

Kamesh Surendran, Ph.D., has been head of a lab at Sanford Research for eight years. He has been studying various aspects of the kidney since his graduate work, including kidney injury and repair.

“We still have a lot to learn about how our kidneys develop and are maintained,” Dr. Surendran said. Exploration of that process drives his lab team’s research. They use mice to study what can go wrong in kidney development, and how that can result in pediatric diseases.

Jennifer deRiso, a research specialist in the Surendran lab, has been working on shifting away from mouse models to establishing a cell culture instead — growing the cells under more controlled conditions outside of an animal.

The kidney’s collecting ducts help regulate water, salt, hydrogen and bicarbonates in the blood to achieve a good balance — to get rid of excesses and alleviate deficiencies, Dr. Surendran explained. Specialized cells help with this process by becoming either water regulators or pH regulators.

Researchers have discovered that these specialized cells can actually switch their roles, even in maturity.

For example, lithium, which can be used to treat bipolar disorder, is thought to cause a side effect in which the patient’s urine can’t concentrate. Dr. Surendran’s lab published a paper in 2019 based on mouse model research showing that water-regulating cells that were given lithium for a length of time then switched roles to pH-regulating cells. If water-regulating cells quit doing their job, that could explain why urine won’t concentrate.

How and why are the cells set up to potentially switch roles? That’s what Dr. Surendran’s lab wants to figure out, with help from Johnson’s summer work. The current hypothesis: This switch can help the body respond to a change in diet — to have the right balance of regulators for the task at hand.

Internship with ‘real project’

So far, they can grow water-regulating — called principal — cells in culture. They haven’t quite determined the right conditions to grow the pH regulators, or intercalated cells, that way. But it would be useful to grow cells outside of the mice to more easily identify the factors that maintain the types of cells and their switching process.

And that’s where Johnson came to play a role. “It’s a real project” that she worked on, Dr. Surendran said. “It’s a real challenge, and it’s doable.”

Johnson started her PROMISE Scholar internship concerned that one biology class wasn’t enough for the job.

But deRiso, who served as Johnson’s mentor by her side throughout the summer, started off by describing the focus of their kidney research and types of cells. She assigned some readings to Johnson. She also created a flowchart to for her to follow.

“Jen is awesome,” Johnson said. “She sat me down and just explained everything to me, so then I definitely understood better.”

It helped Johnson get a better sense of how she would be a part of the lab’s research efforts.

“What I’m trying to involve her in is just having her be a part of something and to make her aware that she’s not working on washing dishes or sweeping up,” deRiso said. “This is something real. This is something big and a part of our project and important to push the project forward.”

Johnson attended a biology “boot camp” to help kick off her internship and attended weekly lectures throughout the summer on topics related to research and presentations. With her team, she participated in lab meetings, and she had one-on-one check-in meetings with Dr. Surendran. She also met weekly with the other three PROMISE Scholars.

Working together

Day in and day out, though, it was deRiso who led Johnson through her lab work and helped her prepare for her poster presentation.

DeRiso, who has a master’s degree in cell and molecular biology, came to Sanford Research five years ago after working for companies in microbiology and in research and development. She appreciates the educational atmosphere of Sanford Research.

“There are people giving talks about what they’re working on all the time, so you’re always drinking in new information,” deRiso said.

Then you naturally consider how you might be able to apply their insights to your own science, she added.

Even at the beginning of Johnson’s internship, deRiso recognized her interest and willingness to learn.

“She’s ready to go,” deRiso said. “She’s going to tell you what she’s thinking about right then and there. I think it’s fun. It’s kind of a neat place to be, to be able to show somebody your world and get them interested in it.”

And others in the lab treated her as an equal — “part of the team,” deRiso said.

Failing and problem-solving

By the halfway point in her summer PROMISE Scholar internship, Johnson had gained a lot of confidence in the lab.

She had become used to working full-time hours. Lab procedures that once made her nervous turned into a breeze. She could easily outline her role in the lab’s overall research project. She had started working on her poster. And she had transitioned from the precise measurements and definitive answers of chemistry to the more relaxed measurements and less definitive answers of biology.

She also learned how to cope with the frustration of not getting a yes or no answer.

“You want a certain result and everything to be perfect,” Johnson said, “and then you do it, and you’re like, ‘No, this didn’t really work.’ ”

“In science, we fail constantly,” Dr. Surendran said, “and what we need to do is learn from that failure.”

“That’s basically what this job is: It’s problem-solving,” deRiso said. “Something didn’t work. Now what do we try? And then you get something to work, all right, now we’ll do the rest of them that way.”

Johnson appreciated the amount of independence she was given to perform lab procedures such as feeding cells, or transferring the cells from one growth culture into a fresh growth culture.

Her role then involved extracting, or purifying, RNA from the cells, she explained. She did tests to try to determine whether the RNA was expressing certain genes and, from that, determine what types of cells they were.

Learning and relating

Johnson developed a much clearer picture of what research is and how it aims to help humans.

At first, Johnson said, “I thought it was just creating drugs, and that was it. ‘Here’s cancer cells. Treat them with this drug. See if it works,’ was kind of the research I had in my mind.”

In her lab, she learned how growing cells in a lab is important — that it could ultimately lead to a better understanding of a disease that affects the kidneys.

Johnson, who has had a special interest in the brain, gained insight from other labs as well.

“I didn’t really know much about the neurological side of research — what they do with the mice, and all the different ways to figure out how to test them, and run through treadmills, or do all this other stuff. I had no idea. So I’ve definitely gotten interested in that,” she said.

Johnson also developed a close relationship with the other three PROMISE Scholars from Sioux Falls area schools throughout the summer.

They enjoyed lunches together at noon, talking about how their mornings went and what they planned to work on in the afternoons. They spent time outside of work on group chats and hanging out.

And they formed a bond that grew from shared experiences, Johnson said. For example, only another researcher might fully appreciate this type of statement, from someone who spent the day on their feet: “I was in cell culture all day, and my legs hurt.”

“I got so close to the scholars this year, and I would’ve never met them before,” Johnson said.

Enlarge

Culmination: Poster presentation

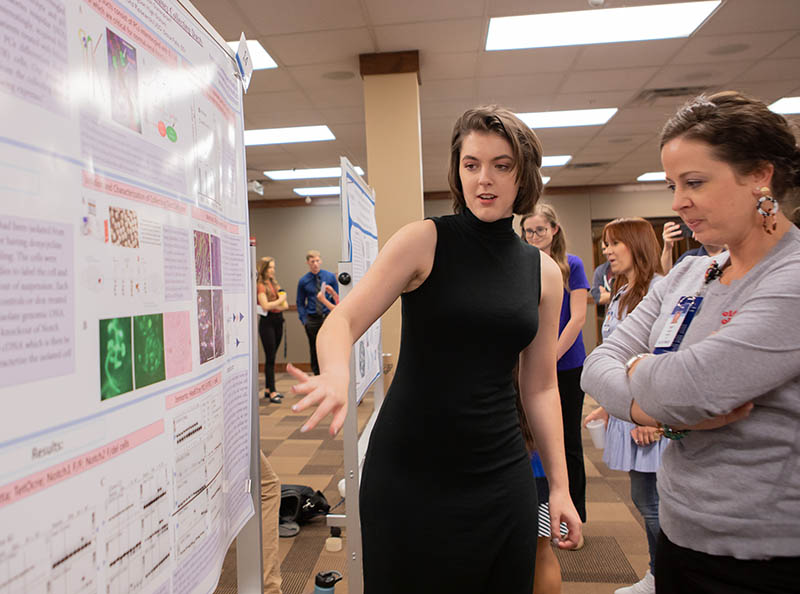

On the last day of her internship, Johnson came to work wearing a black dress and heels. Many members of her family showed up, too.

That morning, the PROMISE Scholars joined SPUR (Sanford Program for Undergraduate Research) students for the student research symposium at Sanford Research. The high school and college students displayed posters describing their research results from their summer internships. They also were available to answer questions that symposium visitors might have about their research. Visitors included family and friends of the students as well as scientists at Sanford Research and other interested guests.

Johnson looked poised and confident as she talked with people and stood next to her poster.

Dr. Surendran was happy to see Johnson’s efforts and the support of her family. “I think they were kind of amazed with what she was able to do over the summer,” he said. “And she presented well.”

At the beginning of the summer, Johnson’s goal for the research symposium had been this:

“I don’t want to present something and just have it be words that someone else has told me to say. I want it to be like I understand what I’m saying and I’m excited to tell you what I’ve learned.”

She certainly accomplished that in her summer of newfound skills, knowledge and effort. Titled “Characterization of Cell Lines Isolated from Mouse Kidney Collecting Ducts,” the poster credited Johnson as first author, followed by deRiso and Dr. Surendran.

Johnson had started her poster halfway through the internship. Even though her experiments were still in progress, she wanted to get started setting up the background and making labels.

Johnson had help from deRiso to structure the poster, and eventually, Johnson could add her results.

Results: ‘This is actually really cool’

The hope of Johnson’s research had been to grow those finicky intercalated cells in a culture. The results of her research turned out not quite as clear-cut.

One major cell line she finished culturing turned out to be in an intermediate stage — considered neither principal nor intercalated. “It wasn’t expressing any genes that we thought it would,” Johnson said.

Another cell line showed more promise. “We think it’s in an early intercalated stage,” Johnson said. “So they’re going to work more on taking that early cell line and then putting it in different environments to try to make it mature.”

At first when Johnson looked at her results, she felt disappointed that she didn’t have mature intercalated cells to show for her internship.

“Then once I actually understood the results, I’m like, wait, this is actually really cool. We got something.”

And while she has returned to high school, Johnson’s lab work will be carried on by others.

Life and career lessons

Johnson made some discoveries about herself over the summer.

For example, she started her PROMISE Scholar internship unaware of how much she values routine.

In the middle of the summer, Johnson talked about appreciating that every day is different in the lab, and that her schedule was never the same. But by the end, after experiencing some days that involved some waiting before moving to the next step in a procedure, she realized that having a schedule really matters to her.

“I want to be able to plan everything every day and have it set for a week,” Johnson said. It doesn’t quite work that way in research, when you often wait for the results to guide your next step.

Johnson had begun the summer with a definite plan to attend the University of Minnesota in the Twin Cities, majoring in neuroscience. She hadn’t decided whether she wanted to go into research or the clinical side of medicine.

She’s still certain about her dream college. But, much like her cells, Johnson didn’t have the most definitive summer in terms of career decisions.

That’s actually a good thing. After a summer of soliciting career advice from researchers — especially Dr. Surendran — Johnson has opened up to other possibilities of majors. She’s still interested in neuroscience, she said, but she has gained confidence, and interest, in considering more biology-oriented majors now. And after her undergraduate degree, a medical degree still strongly attracts her — or maybe even a combined M.D./Ph.D. degree.

Valuable early exposure

Johnson, who plans to work in research in college, has gained skills that surpass her high school peers.

“I know how people work in the lab and the different procedures,” she said. “Maybe I don’t go further in the kidney (field), but at least I know how to do it and how to write down notes, or how to use a microscope, or how to grow cells, which could be viable to any different lab.”

Dr. Surendran considers this early experience, and exposure to a variety of researchers at different education levels, valuable for helping with career decisions.

“I don’t think I stepped into the lab until I was well into my undergrad” years, he said.

Amy Baete, director of K-12 PROMISE Science Exploration at Sanford Research, explained how research fits into the overall medical field.

“A lot of the researchers here have some of the same goals as a medical provider, but there isn’t patient care involved. And a lot of the students that come through this program have an opportunity to see this is a way to contribute to medicine without being in that traditional provider role,” Baete said.

“Some of the students come through realizing that they don’t want to do this because they actually see what it is,” Dr. Surendran said. “So I think that that is maybe the most important thing that they figure out, whether they want to do this kind of a thing or not.”

‘What science really is’

Dr. Surendran values the new thoughts and ideas that can come from the high school and college students as well. Those may come once students get comfortable with the lab atmosphere and start asking questions of their own.

He also enjoys introducing them to the creative aspects of science.

“I like to show them what science really is, as it is — the mess that it is, and also the fun that it can be,” he said.

“That’s actually the exciting part, to kind of figure out the puzzle, how to put it together.”

“Our job can be fun,” deRiso agreed. “I guess you have to be of the science mind to consider it fun, because we’re all little nerds and geeks at heart.”

Watching Johnson and deRiso interact, they clearly did have fun together during the summer.

“I appreciate your honesty and your sense of humor,” deRiso told Johnson. “Those things go so far when you’re sitting in a windowless room for 10 hours a day, and sometimes in a small space in the dark for several hours.”

“The microscope room,” Johnson explained as they both laughed.

Learn more, and apply

Baete asks students curious about research and learning opportunities to ask questions.

“We encourage them to email or call us and talk through what they’re interested in and how we can help them.

“We’ve helped students with science fair projects. Students come in and shadow just to learn a little bit more about what we do here and if that’s something that they’re interested in.”

Johnson urges other high schoolers to consider applying for the Sanford PROMISE Scholar opportunity as well.

“It was an awesome time. I got to meet a bunch of new people and I tried a bunch of new stuff. I … got really close to people in my lab and then got close to the scholars, and I was not expecting that. I thought it was just going to be straight work,” she said.

“The benefits that it has in the future and what you can learn from it is just going to be so much better than if you want to hang out with friends or sleep in most days.”

More stories

- Sanford PROMISE Community Lab shows kids they can do science

- Research internship program attracts students nationwide

- Top grants help Sanford Research draw undergrad interns

…

Posted In Internal Medicine, People & Culture, Research