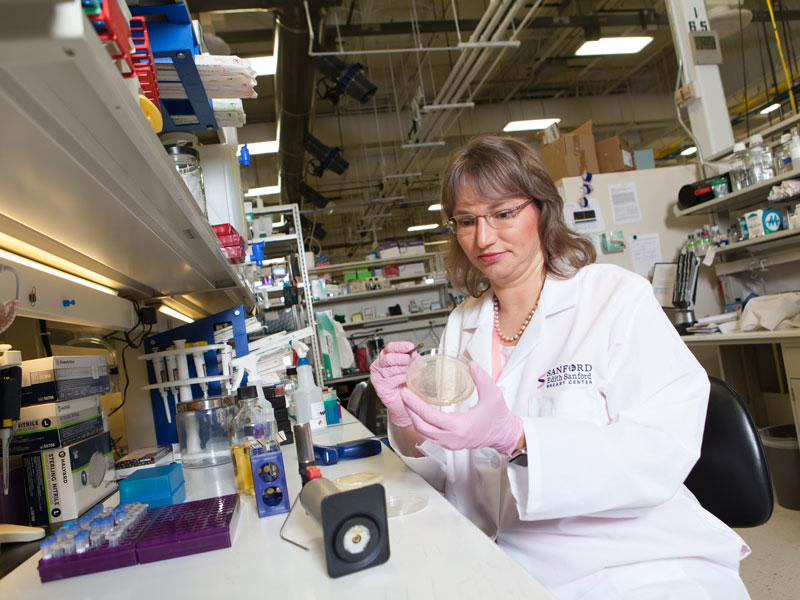

“Wait and see” wasn’t an answer that researcher Kristi Egland could live with.

She couldn’t live with it as a scientist — where her career had focused on identifying targets on the surface of breast cancer cells that could be used for drug treatments.

And she certainly couldn’t live with it after she was diagnosed with stage 3 breast cancer herself.

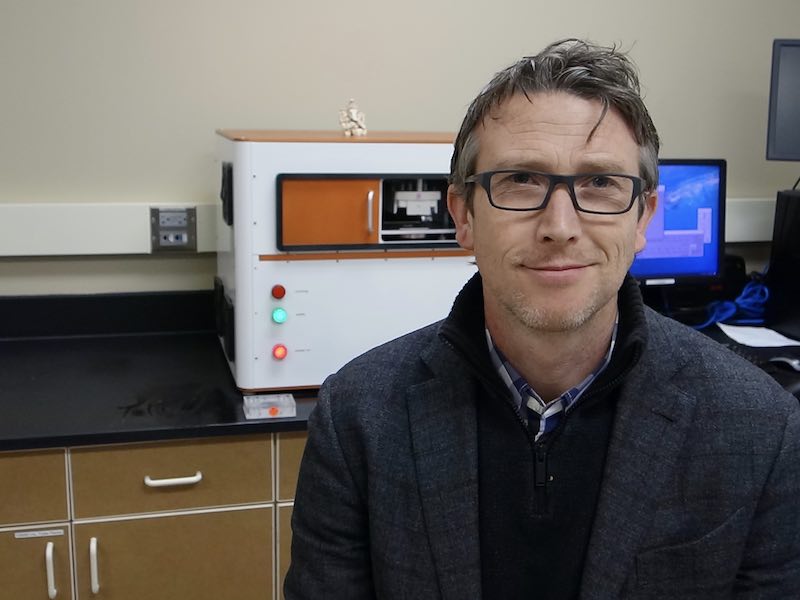

“I was right on the cusp of not being cured, so it was pretty scary,” Egland, Ph.D., says from her office at SAB Biotherapeutics, housed at Sanford Research in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

She went through surgery, chemotherapy and radiation to treat the cancer. But the uncertainty of its return — and at what stage — was unbearable. So far, the main way patients know whether their cancer has returned is when they feel the effects of advanced cancer: pain, a cough that won’t stop, some other persistent problem.

“After having physical symptoms, the physician would say ‘we need to do a scan.’ A tumor is then discovered, and at that point it’s too late,” Dr. Egland says.

So Dr. Egland went back to her lab at Sanford Research, where she was a scientist at the time, and began inventing a test that could discover, before physical symptoms begin to show, if cancer was recurring.

What she didn’t know was that her obsession with solving this problem was coming at exactly the right time for the biotech community in Sioux Falls. The expertise and climate needed to grow a vibrant startup community was just beginning to take off, and the same was true for the atmosphere inside Sanford Health.

“What Kristi did is exactly what we want — take her brilliant idea, and make it happen,” said Kim Patrick, chief business development officer at Sanford Health. “Tapping the talent of our employees and then connecting with the larger business community both locally and nationally is one of our goals, and we couldn’t be happier with this result.”

Photo by Sanford Health

Chance meeting

Dr. Egland had learned while working with antibodies that cells have a memory. Think about vaccinations, which inspire an immune response. Then, if you’re exposed to the same illness, your body remembers what to do.

Dr. Egland thought recurring cancer might inspire a similar reaction, and if she could find it before symptoms appeared, patients might stand a better chance of surviving it.

That’s what she focused on after her treatment was over. In her lab, she had figured out how to mimic proteins in the human body and then detect antibodies against them. Her team was able to identify seven main proteins that may indicate the presence of cancer in a patient.

But any good idea needs to be proven, and then implemented, for it to matter.

A serendipitous discussion with David Ure at a national Small Business Innovation Research conference in Sioux Falls helped complete her puzzle.

Ure founded Inanovate in 2007, originally to sell an improved glass slide to diagnostic companies. But he soon realized that while the slide was better than what was on the market, the real solution was in developing an entire process. And that’s when the BIoID-800 biomarker analysis platform was born.

Next was finding an application.

Cancer diagnostics fit the bill — it doesn’t have a single biomarker, and that variation made it ideal for the test.

“Someone told me about this machine and said, ‘hey, this sounds like your deal,’” Dr. Egland says. “I got so excited. This is exactly what my test needed.”

Dr. Egland describes it as Ure having the smartphone, and Dr. Egland having the app. Together, they could improve cancer testing.

But first, they had to prove it.

Testing at the cell level

Dr. Egland and Ure’s team ran 400 samples through the machine, and that will triple as testing continues. The goal is to detect a difference among women who have cancer, those who are precancerous and those who are benign. Mammograms often trigger false positives, which can be upsetting for patients. The blood test could be another tool for physicians to determine if further testing is needed, and to what extent.

“There are patterns of antibody presence in a patient sample that correlate to cancer,” Ure says. “We are in the process of understanding what those patterns are for breast cancer. If a patient sample presents with such a pattern, then we know we have something.”

The machine is about the size of a large microwave oven that fits on a countertop in the lab. Samples from up to seven patients are placed on a cartridge, inserted in the device and screened by a laser that looks for the presence of proteins in each cell.

“This is a blank sample,” Ure explains as he points to an adjacent computer monitor. “If it was an actual patient sample in process and they had a half dozen or a dozen of those biomarkers present, you would see those biomarkers light up over time as the test was being run. And that’s how you would be able to categorize whether that patient has breast cancer or didn’t.”

The cartridge can hold about 50 biomarkers, and the test takes about an hour and a half to run. Once a threshold is determined, the test will show when someone has a reaction.

Biotech in Sioux Falls

Ure moved the entire company to South Dakota, keeping only the manufacture of the machine in North Carolina, where engineer Greg Votaw designs and builds it in an office-turned-machine shop in his house. He’s on his fifth iteration of the device.

“You learn something every time,” Votaw says.

The Inanovate team has grown to 10 members, and it secured $3.1 million in venture capital financing in 2019 from South Dakota Equity Partners, Denny Sanford and Sanford Frontiers, a corporate affiliate of Sanford Health. The most recent investment builds on a strong year for Inanovate, which included a $2 million Phase 2 SBIR grant from the National Cancer Institute, along with a licensing and collaboration agreement with Sanford Health that provides access to intellectual property relating to a set of breast cancer biomarkers, in addition to patient recruitment and sample access for Inanovate’s trials.

The next step is a pre-market submission to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, planned for 2022, Ure says.

The success of Inanovate points to the continued support and growth of South Dakota’s biotech market, says Aaron Harmon, a developer with the company.

“Our team can take technology and get it into the commercial chain,” he says. “That begins to build the cycle of the biotech industry.”

They found a home at the Zeal Center for Entrepreneurship in Sioux Falls, a nonprofit formed in 2002. The multi-use building in northwestern Sioux Falls offers laboratory and office space where startups can set up and lean on one another for advice, expertise and guidance.

Ure acknowledges that moving from research to product development requires a huge mental shift. But he knew that’s where he had to take the company. Harmon agrees.

“An idea itself will never make it to market without the whole package,” he says.

Tapping internal ideas

That same holistic approach is true for building a pipeline of talent, development and commercialization in a community, a culture that will only benefit employers like Sanford Health in the long run, Ure says.

“We want to see the creation of new companies and new jobs,” says Rick Evans, a project manager with Sanford Health’s business development and commercialization team. “And we have the opportunity to be a major source of health innovation at Sanford Health. We have brilliant physicians and nurses and scientists and people who are capable of making these innovations for medical devices and diagnostics.”

Evans’ role is to help bring ideas to market with inventors and employees at Sanford Health. He’s an audience for ideas, and then helps determine what opportunities are available and what licenses, partners and regulations must be acquired.

He sees it as a valuable tool for employee engagement.

“If you want to compete with the best health care systems in the world, you need to have this,” Evans says. “You take their ideas seriously, and if they can find a way to do something better, that’s great.”

It’s taken about a decade for Dr. Egland’s test to make its way from frustrated patient to idea to trial. And there’s still a long way to go before it could become a standard of care that could help ease the fear of recurrence in cancer patients and save lives.

Dr. Egland now serves as a consultant for Inanovate.

“That’s where you’re supposed to be,” Dr. Egland says. “You’re supposed to invent an idea, then find a partner and build a company that’s successful. Then you go and invent something else.”

Read more

- Sanford cancer clinical trial shows improved outcomes

- Clinics share best pandemic ideas on new crowdsourcing tool

- Collaboration helps Sanford Health test new technology

…

Posted In Cancer, Cancer Screenings, Imaging, Innovations, Sioux Falls, Specialty Care, Women's