In Ethiopia, Eskedar Yimer worked as a civil engineer helping to build roads and bridges. In Sioux Falls, South Dakota, she found a way to follow her heart’s desire into medicine. And moms and newborns staying at Sanford Health’s Birth Place have benefited ever since.

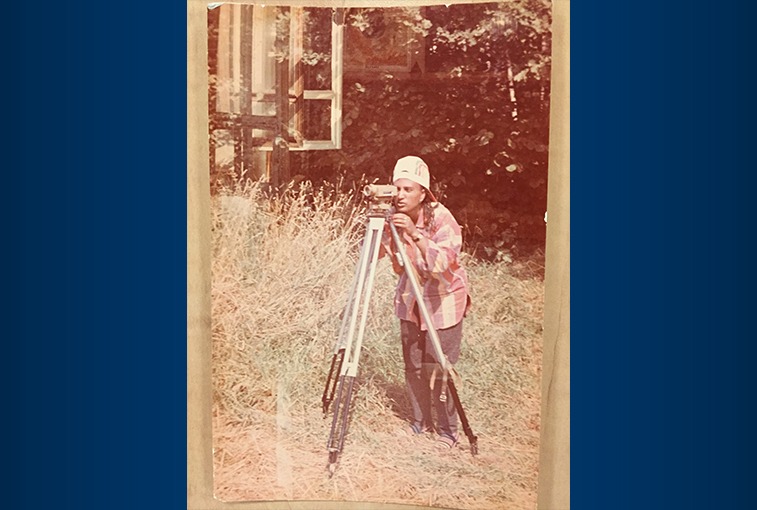

Yimer’s determination and quiet intelligence shine through in a conversation as she traces the path of a girl who grew up in Addis Ababa, received a master’s degree in civil engineering in Moscow, and years later ended up in Sioux Falls raising kids while working full time and going to nursing school.

Her patience and calming demeanor, traits admired by her colleagues, emerge as she checks vital signs on a patient and her newborn son, then shares in the family’s lighthearted reminiscence about the birth that occurred less than 24 hours before.

An engineer, by way of Moscow

Yimer, now 48, was born and raised in the capital city of Ethiopia. Her father was a physical education teacher and later worked for the country’s soccer federation. Her mother took care of her and her five siblings. However, when her father’s work took the family to a cooler climate in Ethiopia, Yimer became sick often enough that she moved back to Addis Ababa to live with her grandmother. She rejoined her family in eighth grade when they moved back to the capital city.

“I always wanted to be a medical doctor,” Yimer remembered. But Ethiopia didn’t offer Yimer and other students complete freedom to choose their career path. So when Yimer’s test scores and GPA indicated she should study civil engineering after high school, she did.

Yimer spent a year in college in Ethiopia but then received a scholarship to study at the Moscow Automobile and Road Construction Institute. She spent six years there, ultimately earning a master’s degree in civil engineering.

Then she returned to Ethiopia for four years, leaving behind the cold winters of Russia but retaining a sense of adventure. After spending a short time in a remote area for her first job, she started working for the Ethiopian Roads Authority’s Department of Construction division, charged with making sure that foreign companies given contracts for road projects did their job well.

And then Yimer’s aunt in America had an idea, and life took a completely new direction.

Moving to Sioux Falls: ‘Where is the city?’

Yimer’s aunt in Maryland applied for opportunity visas, offering the chance to come to the U.S. with two years of work experience, for Yimer’s whole family.

“I was the only one who was chosen to come,” said Yimer, who by then had married a fellow civil engineer and given birth to a son.

The idea of moving to America didn’t intimidate Yimer, who had already lived apart from family in Moscow. So her young family moved to Maryland, where she thought she could find a job right away. When that didn’t happen, a friend of her parents’ who lived in Sioux Falls urged them to make their home in Sioux Falls instead.

Accustomed to living among millions of people, Yimer’s first reaction to Sioux Falls was bewilderment. “I kept thinking, ‘Where is the city?’ ” she recalled.

Embracing a new opportunity

Living in a small city like Sioux Falls did give Yimer the chance to learn a new skill: driving. In contrast, in crowded Ethiopia, she had a driver for work, and in Moscow, she walked or rode a bus everywhere.

More importantly, though, living in Sioux Falls renewed her childhood dream. When Yimer learned she would have to take additional classes and certifications to be a civil engineer in America, she saw a new career opportunity instead. She decided she’d rather take classes in something she’d always longed to go into anyway: medicine.

At this point, it seemed like studying to become a doctor would take too long. But when she delivered her second of four children, a daughter, 17 years ago at what was then Sioux Valley Hospital, Yimer had a patient’s view of nursing. And the impression left by her nurses directed the course of her new career.

“The care I received was really, really amazing,” Yimer says. It inspired a new goal: “I need to go back for nursing. I need to pay back.”

When Yimer came to Sioux Falls, she first worked for an electronics manufacturing company, while her now-former husband studied to become a civil engineer in this country.

Yimer spent four years in nursing school and also worked as an OB-GYN nurse aide for Sanford Health. Her new path wasn’t easy. Her general classes went fine, she said, but “once I was in the nursing program, that was the toughest.”

One obstacle turned out to be her lack of knowledge about basic over-the-counter medications such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen — terms common to her American-born classmates since they were children. “I didn’t know those, so I had to learn everything,” Yimer said.

How Ethiopian practices compare

Yimer had learned English starting in middle school and practiced it quite a bit in her civil engineering position in Ethiopia, but a different type of communication proved to be a bigger challenge: learning how to communicate with patients.

In Ethiopia, Yimer said, interaction between the medical staff and patients is minimal. “They don’t sit down and talk to you about what’s wrong,” she said. And patients aren’t told anything about the medications prescribed for them. “It’s just sad.”

'I wish I could go back and voluntarily teach the staff how to take care of patients nicely.' Eskedar Yimer, Sanford Health RN

Also in contrast between the two countries, equipment such as CT scanners might be found in just a couple of hospitals there. And patients must wait much longer to see a specialist. Ethiopian facilities do offer services such as dialysis now, but for complex surgeries, such as those involving the heart or brain or organ transplants, patients have to leave the country for treatment.

Yimer’s youngest sister works as an OB-GYN in Ethiopia, so they sometimes compare notes about medicine in the two countries. Yimer said that when her sister had a baby, she chose to have a caesarian section. But she left the hospital the following day; since the staff wouldn’t do much for her there, Yimer said, she figured she might as well go home.

“I wish I could go back and voluntarily teach the staff how to take care of patients nicely,” Yimer said.

Working with new moms

When Yimer finished nursing school and clinicals, the new registered nurse eagerly took a job in the same place that inspired her to enter the field. Praise for her Birth Place co-workers, patients — “very appreciative patients” — and caring mentors comes easily.

She tends to work more with moms who are in active labor and delivering their babies, but she’s cross-trained to also work in the postpartum area, where moms and babies typically spend the remainder of their hospital stay. In either place, she enjoys working with patients at a monumental time in their life.

“It’s very exciting to have a baby and meet a new family member,” Yimer said.

When Yimer starts her nighttime nursing shift in labor and delivery, she looks forward to getting to know the patient she’ll be caring for that night. She starts out assessing where the patient is in the process. She talks with the patient about what lies ahead — about pain in early labor; the birth plan, if there is one; and whether there were problems with any previous deliveries. And she talks with the patient about what she wants to happen after the birth: Skin-to-skin contact? Breastfeeding?

‘I’m a calm person’

Through it all, Yimer’s demeanor helps set the tone.

“I’m a calm person, and I think that calmness helps a lot,” Yimer said.

Fellow Sanford Health nurse Sylvia Schwarting agreed. When asked about qualities that a good labor and delivery nurse might exhibit, she listed: patient, empathetic, strong, wise, “sometimes a little bit bold.” Yimer, she said, has those qualities.

“She’s very calming. She’s very knowledgeable. I think our patients trust her. They all like her,” said Schwarting, who has been a nurse for 31 years.

You can’t underestimate the importance of trust. “I think you need to be able to trust the nurse and the doctor that are going to lead you through the process,” Schwarting said. “You have to be able to trust a stranger.”

The nurse doesn’t take that trust for granted, either. “It’s a responsibility. You always want to give your best to the patient. You want it to be a great experience. You want it to be as good as it can be,” she added.

Co-workers ‘are like family’

Yimer helps provide that experience, according to her supervisor, clinical care leader Abby Walton. Yimer acts attentive, calm and reassuring, and she explains things to the patients, Walton said. Bonus: “She’s always looking for something to do.”

Walton and Yimer work nearly every shift together. They have worked together for more than a decade in The Birth Place, starting as nurse aides at the same time.

“She’s just so attentive to her patients and anticipates their needs, so they just feel, I’m sure, well taken care of,” Walton said.

The doctors and nurses who work so closely together “are like family,” Yimer said. “What I like most is the trust we have.”

Her family of close colleagues values Yimer for more than her work, though. Walton said hearing about Yimer’s culture and experiences has been eye-opening for them. “She’s taught us a lot.”

“She’s a special lady. It’s really interesting to hear her stories and her perspectives on life.”

Helping deliver baby Thomas

Yimer had a connection to one recent labor and delivery patient, Danielle Svartoien of Brookings. As it turned out, Yimer had been in the delivery room with Svartoien’s sister a few weeks before. When Svartoien’s sister arrived back again, this time to offer support, she and Yimer recognized each other and reminisced about her experience as a patient.

For Svartoien’s delivery, Yimer came into her 7 p.m. shift just a half-hour after Svartoien and her husband, Caleb, arrived at the hospital. Svartoien, already dilated to 7 cm when they walked in, was about to deliver her second child, but under different circumstances than with her first.

Enlarge

Jane Thaden Lawson

With her daughter’s birth two and a half years before, she had been induced. This time, with contractions crowding together and a quickening dilation, the timing of an epidural was in question. Adding to that were memories of a difficult postpartum recovery the first time. “I was scared,” Svartoien said.

But almost 24 hours later, as Yimer started her shift as a postpartum nurse for the Svartoiens, she and the couple talked comfortably in front of a few visitors about how the delivery ultimately went.

They agreed that if baby Thomas, born at 9:57 p.m. the night before, had been in the proper position facing down instead of up, he could have arrived much sooner. But that also could have interfered with Svartoien’s deep desire for an epidural. However, because of his posterior position — unknown at first — Svartoien was able to get an epidural, the doctor broke her water, and her mom and two sisters had time to arrive for photography and cheer duty. Svartoien started pushing about 9:15 p.m. When nothing happened, Thomas’ position was discovered, and the doctor turned him. And then he arrived.

Yimer helped guide the family through the process. “She was good at explaining what was happening and going to happen,” Danielle Svartoien said.

At just over 8½ pounds, Thomas weighed enough to warrant checking his blood glucose levels, to be sure they weren’t too low. So Yimer educated the family about how glucose levels work and why monitoring them matters. She also helped clean Danielle up, position her in a wheelchair and transport her to the postpartum area.

“Everyone was super nice, even when I was freaking out about the epidural. They were telling me it was going to be OK,” Svartoien said.

A night’s work for Yimer

Getting to know and guiding a woman at one of the most vulnerable times in her life. Monitoring her progress and honoring her dignity. Welcoming her support team of family and friends. Encouraging her when she’s beyond worn out. Witnessing the first breaths of a brand-new being and the tender love binding parents to newborn.

It’s all in a night’s shift for Yimer, now a U.S. citizen.

“I’m fortunate to be here and to have an experience as part of Sanford to give care that’s needed from me, and to receive care,” she said.

Ethiopia lost someone who helped build roads. But we gained someone who helps build families.

More

- Labor nurses bring calm to storm of new motherhood

- Former patient becomes nurse because of childhood care

- Learn secrets for an easier labor and delivery

- Sanford Health has a variety of job openings for registered nurses

…

Posted In Brookings, Gynecology, Pregnancy, Sanford Stories, Women's